In Illinois How Much Money Can Inmates Have In Their Accounts?

The Company Store:

A Deeper Look at Prison house Commissaries

By Stephen Raher Tweet this

May 2018

Printing release

Prison commissaries are an essential but unexamined office of prison life. Serving every bit the core of the prison retail market, commissaries present yet another opportunity for prisons to shift the costs of incarceration to incarcerated people and their families, often enriching private companies in the process. In some contexts, the financial exploitation of incarcerated people is obvious, evidenced past the outrageous prices charged for simple services like phone calls and email. When it comes to prison commissaries, yet, the prices themselves are not the trouble and so much as forcing incarcerated people — and by extension, their families — to pay for basic necessities.

Agreement commissary systems tin can be daunting. Prisons are unusual retail settings, information are difficult to find, and it's hard to say how commissaries "should" ideally operate. As the prison retail landscape expands to include digital services similar messaging and games, it becomes even more hard and more of import for policymakers and advocates to evaluate the pricing, offerings, and management of prison commissary systems.

The current study

To bring some clarity to this bread-and-butter issue for incarcerated people, we analyzed commissary sales reports from state prison systems in Illinois, Massachusetts, and Washington. We chose these states because we were able to easily obtain commissary data, but conveniently, these three states also represent a decent cantankerous section of prison house systems, encompassing a diverseness of sizes and different types of commissary direction.1

We plant that incarcerated people in these states spent more on commissary than our previous inquiry suggested, and nigh of that money goes to food and hygiene products. Nosotros also discovered that even in state-operated commissary systems, private commissary contractors are positioned to profit, blurring the line between state and private control.

Lastly, commissary prices represent a meaning fiscal burden for people in prison, even when they are comparable to those establish in the "free earth." However despite charging seemingly "reasonable" prices, prison retailers are able to remain profitable, which raises serious concerns nearly new digital products sold at prices far in excess of market rates.

How much do incarcerated people spend in the commissary?

In Illinois and Massachusetts, incarcerated people spent an average of over $1,000 per person at the commissary during the class of a twelvemonth. Annual per capita sales in Washington were nigh half as much.2

| Illinois | Massachusetts | Washington | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almanac Commissary Sales | $48,416,118 | $eleven,713,446 | $8,696,721 | |

| Avg Daily Prison house Popular | 43,199 | 9,703 | 16,943 | |

| Per-person Annual Sales | $1,121 | $1,207 | $513 | $947 |

| Commissary operator | State Doc | Contractor (Keefe) | State Physician |

Per-person commissary sales for the three sampled states amounted to $947, well over the typical amount incarcerated people earn working regular prison house jobs in these states ($180 to $660 per year). The per-person sales were also college than a previous survey had suggested.three In 2016, we estimated that prison house and jail commissary sales corporeality to $ane.6 billion per year nationwide, based in part on data from a 34-country survey past the Association of State Correctional Administrators. Just the more recent and more than detailed information presented in this study propose that commissary might be an even higher-grossing industry than we previously thought.

There were important state differences in commissary sales, however. Washington's per-person boilerplate was dramatically lower than the other two states'. The reason for this difference isn't entirely clear, simply it seems that personal belongings policies issued by the Department of Corrections are at least partially responsible for this significant disparity.

What are people buying?

Almanac per-person sales averages just tell part of the story. We also wanted to expect closely at what people were spending their money on. To practise this, nosotros obtained detailed inventory reports from the 3 commissary systems and categorized (when possible) each inventory detail and its commensurate sales figures.4

| Illinois | Massachusetts | Washington | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sales past Category | Total | Per Person Annual Avg | Total | Per Person Annual Avg | Total | Per Person Annual Avg | ||

| Clothing | $three,266,773 | $76 | $269,026 | $28 | $xx,131 | $1 | ||

| Electronics | $three,068,081 | $71 | $343,033 | $35 | $15,011 | $1 | ||

| Food & Beverages | ||||||||

| Beverages | $4,282,535 | $99 | $1,600,411 | $165 | $one,492,599 | $88 | ||

| Condiments | $i,449,613 | $34 | $533,407 | $55 | $338,344 | $20 | ||

| Ingredients | $four,174,084 | $97 | $897,286 | $92 | $1,273,352 | $75 | ||

| Set Food | $15,429,178 | $357 | $iii,402,365 | $351 | $2,102,377 | $124 | ||

| Snack Nutrient | $8,968,413 | $208 | $2,688,722 | $277 | $1,466,314 | $87 | ||

| Subtotal - Food & Beverages | $34,303,823 | $794 | $9,122,192 | $940 | $vi,672,986 | $394 | ||

| Household goods & Supplies | $1,957,080 | $45 | $269,560 | $28 | $95,236 | $6 | ||

| Hygiene & Health | $3,446,257 | $lxxx | $929,893 | $96 | $i,547,409 | $91 | ||

| Post & Stationary | $1,196,758 | $28 | $468,231 | $48 | $345,947 | $20 | ||

| Unknown/Unclassified | $1,177,346 | $27 | $311,511 | $32 | $0 | $0 | ||

| Total | $48,416,118 | $1,121 | $eleven,713,446 | $1,207 | $8,696,721 | $513 | ||

Not surprisingly, food dominates the sales reports; prison and jail cafeterias are notorious for serving small portions of unappealing food. Another leading problem with prison house food is inadequate nutritional content. While the commissary may help supplement a lack of calories in the cafeteria (for a price, of course), it does not compensate for poor quality. No fresh food is available, and most commissary food items are heavily processed. Snacks and ready-to-eat food are major sellers, which is unsurprising given that many people need more food than the prison provides, and the easiest — if not only — alternatives are ramen and candy confined.

These data contradict the myth that incarcerated people are buying luxuries; rather, most of the little money they have is spent on basic necessities. Consider: If your just bathing option is a shared shower area, aren't shower sandals a necessity? Is using more than i ringlet of toilet paper a calendar week really a luxury (especially during periods of intestinal distress)?5 Or what if you accept a chronic medical condition that requires ongoing use of over-the-counter remedies (e.chiliad., antacid tablets, vitamins, hemorrhoid ointment, antihistamine, or heart drops)? All of these items are typically only available in the commissary, and only for those who can afford to pay.

Bringing this give-and-take into the realm of the concrete, consider the following examples from Massachusetts. In FY 2016, people in Massachusetts prisons purchased over 245,000 bars of lather, at a total price of $215,057. That means individuals paid an average of $22 each for soap that year, even though DOC policy supposedly entitles them to one free bar of soap per week.vi Or to have a different example: the commissary sold 139 tubes of antifungal cream. Accounting for gross revenue of only $556, the commissary contractor is obviously not getting rich selling antifungal cream, no matter the mark-upwardly—instead, the point is that information technology's hard to imagine why anyone would buy antifungal foam other than to treat a medical condition. Notwithstanding Massachusetts has forced individual commissary customers to pay for their ain treatment, at $four per tube, which can represent four days' wages for an incarcerated worker.vii

How practise incarcerated people afford commissary?

For many people in prison, their meager earnings get correct back to the prison commissary, not unlike the sharecroppers and coal miners who were forced to use the "company store." When their wages are non enough, they must rely on family members to transfer money to their accounts — significant that families are effectively forced to subsidize the prison organisation.9 Others in prison who lack such support systems just can't afford the commissary at all.

While the sales data permit the states to calculate average commissary expenditures per person using the total prison population, this number does not tell the whole story: It flattens the spending gap between prisoners who tin "afford" to buy from the commissary versus those who cannot.

The poorest people in prison, such every bit those considered "indigent"ten by the state, spend lilliputian to nothing at the commissary. This, in plough, means that the per capita spending for all others is actually greater than the average numbers reported above. We can get a very limited glimpse of this population by looking at Washington, where commissaries stock certain items that are available simply to people who qualify as indigent. Based on annual sales of "indigent toothpaste" and "indigent soap," information technology appears that a significant portion of people in Washington's prisons (betwixt about ten percent and one-3rd) are indigent.

How "fair" are gratuitous-globe prices in a prison?

Analogy by Elydah Joyce

Analogy by Elydah Joyce

Ane rather surprising finding is that prices for some common items were lower than prices plant at traditional free-world retailers.11 Other commissary prices were higher, but merely by a little bit. (Meet Tabular array 3.)

This isn't to say that prison house commissaries are in the business of providing bargains. Rather, it is a natural result flowing from the fact that a regular retailer has substantial costs (such as operating a network of retail outlets and advertising) that don't ascend in the prison context. In fact, a prison commissary is somewhat analogous to an online retailer like Amazon: goods motility directly from a warehouse to the customer, without the expenses associated with maintaining a traditional retail presence. In addition, commissary operators accept a legal monopoly, so they don't have to worry about toll competition, and thus practice not incur costs associated with special sales or discounts.

| Item | Illinois | Massachusetts | Washington | Amazon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commissary | Local Retail | Commissary | Local Retail | Commissary | Local Retail | ||||||

| VO5 shampoo 12.v oz. bottle | $ane.25 (LIN) to $1.69 (VIE) | $0.99 (Jewel, Chicago) | $ane.38 | $1.29 (Star Market, Cambridge) | $ane.71 (no size specified) | $1.19 (Bartell's Drugstore, Seattle) | $4.88 | ||||

| Bic twin razor (unmarried) | $0.12 (HIL) to $0.18 (LIN) | $0.35 (based on $three.49 for pkg of x) (Jewel) | $0.15 | Unable to locate; comparable product (Gillette) available @ $1.20 (based on $11.99/pk of ten) | $0.22 | $one.20 (based on 5.99 for pkg of 5) (Bartell's) | $0.57 (based on $5.72 for pkg of 10) | ||||

| Maruchan beef ramen | $0.25 (multiple locations) | $0.34 (based on $1 for pkg of iii) (Jewel) | $0.40 | $0.59 (Star Market place) | $0.25 or $0.29 (no brand specified) | $0.89 (IGA Seattle) | $0.71 (based on $16.99 for instance of 24) | ||||

| Mrs. Dash 2.5 oz. bottle | $2.98 (multiple) to $iii.26 (multiple) | $two.99 (Gem) | $2.forty | $3.49 (Star Market place) | non available | $4.09 (IGA Seattle) | $two.94 | ||||

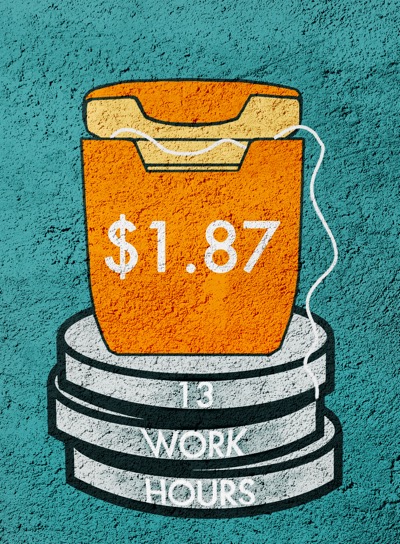

The other matter to keep in mind when comparing commissary prices to the complimentary world is that people in prison have drastically less money to spend. And then, while $i.87 may sound similar a fair price to pay for a month'southward worth of dental floss, the transaction feels very different from the perspective of someone in a Massachusetts prison who earns xiv cents per hr and has to work over 13 hours to pay off that floss.12 Or, to consider a different scenario: the boilerplate person in the Illinois prison house system spends $eighty a twelvemonth on toiletries and hygiene products — an corporeality that could easily represent nearly half of their annual wages.13

Privatization can take different forms

When a prison organization's commissary is run by a private company, information technology raises logical concerns about fairness and coercion. In 2016, when ane of the largest prison house food service/commissary companies (Trinity Services Grouping) merged with another dominant commissary company (Keefe Group), we expressed concerns about the concentration of power and diminished competition — and quality — that would result. The passage of time has confirmed these fears: by 2017, maggots, dirt, and mold were reported in meals served by Trinity; these quality problems along with small portions led to multiple prison protests and $3.8 million in fines for contract violations in Michigan alone.

But exploitation tin occur even if a arrangement is non fully privatized. Of the iii states we examined, just Massachusetts has a contractor-operated commissary arrangement. It likewise has the highest per-person average commissary spending. It is tempting to conclude that the profit motive of commissary contractors leads to higher marking-ups and thus higher per capita spending, but nosotros would need a larger sample size to exam this hypothesis. What is notable in our three-country survey is that Illinois, with its state-run commissary, had per capita sales about as high as Massachusetts' contractor-run organization, so a state-run system is clearly not a panacea.fourteen In addition, per capita spending in Washington and Illinois are so dramatically different that at that place must exist other meaning factors beyond outsourcing.

Arguably the most important privatization-related information in this written report comes from Illinois. The Illinois prison commissary system has as well been subject to harsh criticism for poor purchasing policies. In a 2011 report on commissary shortcomings, the Illinois Procurement Policy Board noted that simply 19 vendors provided 91% of all the items (measured by dollar corporeality) sold in the commissary. Among this scattering of dominant providers, the 1 with the largest share was none other than Keefe, which deemed for 30% of the commissary's spending. Thus, if Illinois is any indication, it appears that Keefe is positioned to make money even in states that take not privatized the performance of their prison commissaries.

The time to come of commissary: digital sales

Incarceration is becoming increasingly expensive — especially for those backside confined and their families. While prisons find new ways to shift the costs of corrections to incarcerated people (call up medical co-pays and pay-to-stay fees), vendors are aggressively pushing new digital products that volition further monetize incarcerated people.

This new breed of digital sales can take dissimilar forms. Sometimes this consists of "free" computer tablets that offer subscription based music streaming or ebooks. Other times, people must buy tablets or MP3 players and then pay for digital content. Given monopoly contracts and a captive market, prison and jail telecommunication providers are able to generate revenues far greater than similar companies in not-prison settings.

Some states appear to separate digital sales from the prison commissary, while others sell music downloads and other digital content through the commissary. Of the iii states we looked at, Illinois was the only system that included digital sales in its commissary reports. The Illinois DOC contracts with GTL to provide electronic messaging and, apparently, digital music downloads. We say "apparently" because there is no reference to music downloads on the Illinois DOC website, but based on the sales figures, music sales seem to be a substantial coin-maker:

| Description | Inventory Detail | Qty Sold | Gross Sales |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic messaging | Prepaid bundles of 1 or 20 messages | 12,443 | $35,301 |

| Music | Unclear | 82,374 | $838,947 |

| Hardware | MP3 players and accessories | three,171 | $267,550 |

| Full | $1,141,798 |

Cost-gouging in commissaries is concentrated in the digital realm

Illustration by Elydah Joyce

Illustration by Elydah Joyce

The pricing information discussed before provides testify of an of import fact: commissaries tin afford to sell goods at prices comparable to or lower than free-world stores even while arresting extra security-related costs (such equally secure warehouses) and reaping healthy corporate profits. It appears prisons are ignoring these advantages when evaluating the prices of new digital products. Every bit a prime example, the Massachusetts DOC signed a new contract with Keefe about a year ago, which includes electronic messaging and MP3 downloads. In stark contrast to the generally reasonable prices found in the commissary, Keefe's digital music is priced at $i.85 per song, which is far college than prices found on services similar iTunes, Amazon, or Google Music (and more than than tin can be explained past 5¢ kickback the Dr. pockets for each song).

The price disparity for digital items is even more confusing when you consider that delivering an MP3 file raises fewer security concerns than delivering a box of cereal to a prison commissary. The cereal box can theoretically be used to hide contraband, while an MP3 cannot. Of course, operating a digital music platform requires a robust Information technology security programme, but this is truthful of any service, whether it operates in the free world or but in prison. Indeed, in some ways, Keefe has less exposure to IT-based threats because much of its system operates on a closed network of kiosks and MP3 players, over which it exercises complete control (as opposed to Apple, which makes its iTunes store available to pretty much anyone with a figurer and an internet connection). Thus, information technology is both paradoxical and troubling that Keefe can manage to toll junk food and toiletries at or below standard retail prices, just charges nearly double the typical cost for a digital music download.

Conclusion

Although information technology's tricky to say how commissaries "should" ideally operate, their sales records ought to heighten multiple concerns for justice reform advocates. If people in prison house are resorting to the commissary to buy essential goods, like food and hygiene products, does it actually make sense to accuse a day's prison house wages (or more) for 1 of these goods? Should states knowingly force the families of incarcerated people to pay for essential goods their loved ones can't beget, ofttimes racking up exorbitant money transfer fees in the process?

Conversely, when people in prison buy "nonessential" digital services, policymakers should compare the costs of those services to free-world prices. Marking upward the cost of digital services for incarcerated people in lodge to make a quick turn a profit - specially in a time when these services are near-ubiquitous and generally inexpensive - is unquestionably exploitative.

In the long term, when incarcerated people tin can't beget appurtenances and services vital to their well-being, society pays the price. In the short term, however, these costs are falling on families, who are overwhelmingly poor and disproportionately come up from communities of color. If the toll of food and soap is too much for states to bear, they should detect ways to reduce the number of people in prison house, rather than nickel-and-diming incarcerated people and their families.

Acknowledgements

This written report was fabricated possible by the generous contributions of individuals across the country who support justice reform. Individual donors give our organization the resources and flexibility to quickly plough our insights into new movement resources.

The author wishes to give thanks his Prison Policy Initiative colleagues for their feedback and assistance in the drafting of this report. Bridget Doyle, Hannah McKinney, and Sanndy Teran provided research help for toll comparisons in Illinois and Massachusetts. Elydah Joyce created the illustrations.

About the author

Stephen Raher is an attorney in Oregon who works with the Prison Policy Initiative on projects at the intersection of criminal justice and finance or criminal justice and telecommunications. He began volunteering with us in 2015. Since then, he has written extensively well-nigh exploitative prison "services" including electronic messaging," release cards, tablet computers, and money transfers. On the subject of commissaries, Stephen authored a 2016 investigation of the size of the commissary market just every bit ii commissary giants prepared to merge.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-turn a profit non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to betrayal the broader impairment of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more simply society. The organization is most well-known for its large-film publication Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie that helps the public more fully engage in criminal justice reform. This written report builds upon the organisation's piece of work advocating for fairness in industries that exploit the needs of incarcerated people and their families, including those that control prison and jail telephone calls, video calls, electronic messages, release cards, and money transfers.

Footnotes

Source: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/commissary.html

Posted by: ryanandlonimper.blogspot.com

0 Response to "In Illinois How Much Money Can Inmates Have In Their Accounts?"

Post a Comment